Railweb Reports

Europe’s inland terminals in a fast-changing world

Posted by George Raymond on January 9, 2017

New technology, trading patterns and consumer demands are bringing ever-greater complexity and ever-faster change to the world of logistics. Participants at a November 17-18, 2016, conference on inland terminals in Basel, Switzerland, examined how European inland terminals are adapting their roles and organisation in this environment. The conference also focused on collaboration among ports in the upper Rhine valley and the work of a “last-mile captain” in Belgium.

Critical factors for inland terminals are the development of rail and water infrastructure links such as the new Gotthard tunnel, intermodal services, cooperation, digital integration, and the changing roles of logistic providers, port authorities and government.

Except as noted, the author took this article’s photos in the Port of Switzerland in Basel on November 18, 2016.

Cranes of operator Contargo’s two container terminals in the Port of Switzerland’s Basin 2 in Basel.

Cranes of operator Contargo’s two container terminals in the Port of Switzerland’s Basin 2 in Basel.

Contents of this report

| Trends in logistics | |

| Inland terminals | |

| A look at specific inland terminals | |

| Infrastructure links to inland terminals | |

| Transport services to inland terminals | |

| Role of major actors in inland terminals | |

| Examples of good practice with inland terminals |

Trends in logistics

A need for fairness

Alex Van Breedem, CEO of TRI-VIZOR, which organises “carpooling for cargo”, spoke on the future of logistics. He said the average truck speed and fill rate are dropping due to

- Smaller and more frequent shipments

- Shorter lead times

- On-demand customer service expectations

- Societal bans on capacity expansion

- A driver shortage

- E-commerce

Customers who use e-commerce want trucks to come to their domiciles. Extra traffic is being created, for example, by the consumer’s ability to return all the shoes they didn’t like.

Container crane of terminal operator Contargo’s north terminal in Basel’s Port Basin 2.

Container crane of terminal operator Contargo’s north terminal in Basel’s Port Basin 2.

But consumption is not increasingly significantly, Mr Van Breedem said. This means more capacity is required for the same value, or a capacity shortage will develop.

Average truck speeds decreased from 69 km/h in 1969 to 51 km/h in 2016. The average driver is 49 years old. Employing refugees and migrants may be possible, but raises complex problems. Unmanned trucks will not be ready for 10 years. Competition prevents any increases in trucking rates, but shippers will have more inventory costs. Road pricing will become a significant part of the price of transport.

Helge Neumann-Lezius, intra-Europe trade manager for Kühne + Nagel, said that the logistics industry needs to prepare for future restrictions on trucks.

Mr Van Breedem said that all this is leading to a need for “fair logistics”, in which consumers pay a fair – i.e. higher – price for the convenience they demand.

Historical and future trends

Mr Van Breedem presented a timeline for logistics’ development:

- 1990s: internal IT integration and optimisation

- 2000s: IT integration and optimisation with customers

- 2010s: collaborative platforms

- 2050: physical Internet

Imbalanced trade flows remain a constant, however, Mr Van Breedem said. For example, much more freight travels from Spain to the Netherlands than vice versa.

Mr Neumann-Lezius of Kühne + Nagel said that the most important factors affecting logistics between 2010 and 2016 were debt-reduction efforts, the Russians, refugees, Brexit, oil prices, green pressure, and advances in automation, efficiency and IT.

The world container trade has stopped growing, he said, but local markets – such as within China – continue to. Ocean carriers are at zero profit because of overcapacity, which nevertheless continued to grow at 8% in 2016. The situation will continue for the next two to three years. This will lead to much slow steaming at 12 to 13 knots to save fuel and absorb overcapacity.

Mr Neumann-Lezius foresees forced mergers among the 20 shipping companies and more bankruptcies such as Hanjin’s of South Korea. Only three East-West alliances are left.

The Port of Strasbourg’s president, Catherine Trautmann, pointed out that shipments by rail from China are increasing and that the Chinese have a large hub in Belarus.

Libor Lochman, executive director of the Community of European Railways (CER), said that between 2005 to 2013, rail intermodal tonne-kilometres grew by 27% and tonnes by 41%. In this same period, total tonne-kilometres and tonnes for rail both decreased by 3%.

Ever-faster adaptation

Companies and other organisations are being forced to adapt to changing conditions ever more quickly.

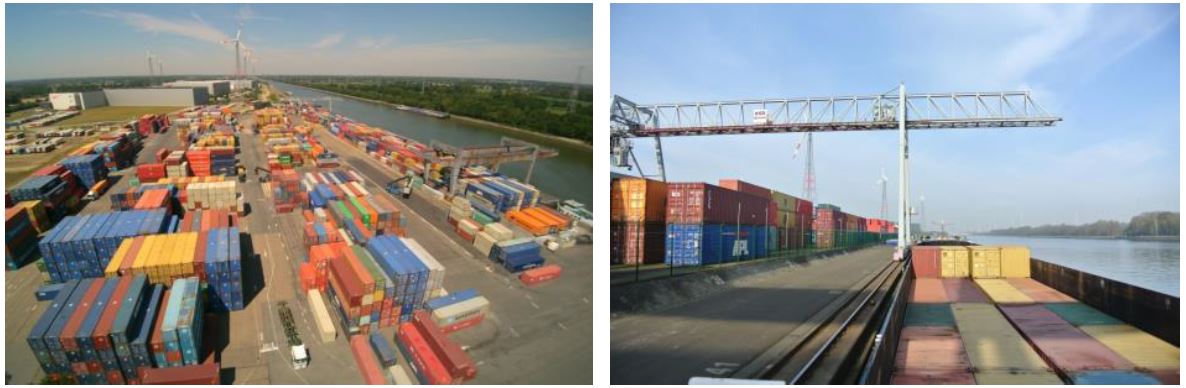

Another view of Basel’s Port Basin 2. Contargo’s south container terminal is in the left background and bulk dry freight is loading in the right foreground.

Another view of Basel’s Port Basin 2. Contargo’s south container terminal is in the left background and bulk dry freight is loading in the right foreground.

Herbert Ruile is professor of international supply chain management at the University of Applied Sciences of Northwestern Switzerland and president of the Swiss logistic association VNL Schweiz. Mr Ruile said that technology is putting pressure on all of us – we have no choice. Global market competition is a fact, not an opportunity. It will bring big bankruptcies. Organisations are being both pushed by threats and pulled by opportunities to change. They need to find a happy medium between continuous and disruptive change, but Mr Ruile sees the biggest opportunities in disruptive change.

The coming of the physical Internet

Mr Van Breedem of TRI-VIZOR said that the physical Internet will offer shorter transit times than today’s individual shipping, but it is still unclear how it will work. It is the key to sharing as opposed to dedicating capacity. Big firms are already doing this. This trend will facilitate intermodal transport.

Peter de Langen, professor at the Eindhoven technical university (TU Eindhoven) in the Netherlands, predicted that the nodes of the physical Internet will be deep-sea and inland ports and that in Europe, the TEN-T network will form its main links.

The challenge of complexity

Mr Ruile said that logistic actors must deal with the following factors:

- Digitalisation and connectivity: In multinational transport chains today, the process among actors is not standardised, and still involves lots of paper and phone.

- Individualisation and additive manufacturing, which may require bringing back manufacturing to Europe from China.

- Autonomy and automation, for example car sharing and room sharing.

- Performance pressures: even individuals now demand just-in-time delivery.

- The Internet of things.

All these factors, Mr Ruile said, are steadily increasing in complexity for organisations in a setting of chaos, ambiguity, volatility and uncertainty. This requires adaptivity and learning in the organisation. Quoting Stephan Hawkins’ statement that “intelligence is the ability to adapt to change”, Mr Ruile described how Alfred Sloan took Henry Ford’s standardisation ideas and differentiated them into big, medium and small cars at General Motors.

To extend its campus to the west bank of the Rhine, the health-sciences company Novartis bought former grounds of the Port of Switzerland for some 100 million Swiss francs from the City of Basel. The public can now walk along the river here. The port retained its main presence in Basel, however, on the Rhine’s east bank.

To extend its campus to the west bank of the Rhine, the health-sciences company Novartis bought former grounds of the Port of Switzerland for some 100 million Swiss francs from the City of Basel. The public can now walk along the river here. The port retained its main presence in Basel, however, on the Rhine’s east bank.

Mr Ruile described the following steps:

- Phase 1: Mass production

- Phase 2: Globalisation, which requires risk management, competition, and transparency

- Phase 3: Digitalisation, which is characterised by individuality, web technology, and social networks, and leads to ever-increasing use of artificial intelligence and big-data analytics

In parallel, Mr Ruile said, companies are going through the following phases in their relationship with suppliers:

- Phase 1: Qualification

- Phase 2: Development

- Phase 3: Integration

- Phase 4: Management of complex adaptive networks of which both client and supplier are members

Mr Ruile said that these changes are likely to be accompanied by the following business model innovations: mixtures of products and IT; spontaneous networking based on plug and play; value-added networks; virtual organisations; and complex adaptive behaviour.

Inland terminals

Factors in deep-sea port choice

Mr Neumann-Lezius of Kühne + Nagel said logistics actors seek visibility and flexibility in supply chains. He named the chief factors in deep-sea port choice:

- Cost of terminal handling

- Costs for trucking, barge and rail

- What’s reachable via one inland terminal

- Distance to producer and end consumer

- Hinterland transit times

Hans-Peter Hadorn, CEO of the Port of Switzerland and president of the European Federation of Inland Ports (EFIP), said that in a deep-sea port, the barge terminal must be close to ocean vessels. An audience member commented that bad connections between ships and barges forces containers onto rail. [Comment by Railweb Reports: And bad barge and rail connections force the containers onto trucks.]

Julian Skelnik, director of the port of Gdansk authority and chairman of the Baltic Ports Organisation (BPO), called the deep-sea port of Gdansk “the last non-freezing port”. Although ships from the Suez Canal reach Koper, Slovenia, 11 days earlier, Gdansk handles some 1000 block trains with 28 operators monthly. Such hinterland services are key to the port’s attractiveness.

Hinterland terminal types and roles

Mr de Langen of TU Eindhoven noted that the Port of Hamburg has fewer inland ports than Rotterdam and Antwerp (along the Rhine), but more hinterland hubs. Lutz Birke, member of the management board of the Port of Hamburg, said the port runs 1200 trains per week to hinterland hubs, including Bavaria, Austria and the Czech Republic, with trains every six hours to Prague.

Mr Hadorn of the Port of Switzerland and EFIP said that the European Commission wants to integrate inland ports and rail terminals. An audience member noted a trend of investments through 2026 to make inland ports into consolidation hubs.

Andreas Janetzko is head of the new inland/intermodal Europe division of DP World. His division is in charge of outsourced terminal operations for inland ports. He pointed to efforts to transform inland ports more into logistic hubs than consolidation hubs.

Inland terminal attractivity

Mr Neumann-Lezius of Kühne + Nagel presented the factors that made an inland hub attractive:

- Efficiency resulting from an adequate volume of water, rail and road traffic

- An IT system offering efficient entry and exit monitoring, customs clearance, general port management, and full visibility – not just to middlemen, but also to cargo owners

- Well-managed connection between ocean and inland services

- Nearby warehouse and logistics facilities

- Low costs

- Ability to maintain awareness of improvements and support services

Discussion revealed that, depending on the local situation, the need for adequate water, rail and road volumes may lead either to shifting, consolidating or expanding inland terminals.

Action at the Contargo container terminal on the south side of Basel’s Port Basin 2. The Rhine is just west of here, under the bridge ahead.

Action at the Contargo container terminal on the south side of Basel’s Port Basin 2. The Rhine is just west of here, under the bridge ahead.

Capacity for peaks is also an issue. Ben Maelissa, managing director of the barge operator Danser Group, said that waterways have no congestion, but inland ports do. Alexander van den Bosch, director of the European Federation of Inland Ports, said that mega-ships create peaks even at inland ports.

Mr Maelissa said that quality of a seaport’s hinterland connections depends on that of its inland terminals. An audience member called the inland terminal the weak link that is decisive for hinterland modal choice.

The role of the port authority

No less than four speakers addressed the appropriate role of the port authority. Mr Birke of the Port of Hamburg said port authorities have marketing teams that promote and perform consultancy, but only port operators sell. Mr van den Bosch of the European Federation of Inland Ports said an inland port needs to go from being a landlord to being an organiser of transport flows, and set the right conditions. Mr de Langen of TU Eindhoven saw a need for a neutral operator and moderator among all the actors around the port. The port authority should do business development, but must leave sales to the market. Mr Maelissa of barge operator Danser said that the port must serve as a mediator.

A look at specific inland terminals

The Port of Switzerland

Facilities of the Port of Switzerland are located at several sites along the Rhine in the Basel area.

Entry watch of the Port of Switzerland site in Basel.

Entry watch of the Port of Switzerland site in Basel.

Christoph Brutchin is head of the department of economy, social issues and environment of the Swiss canton of Basel City. He called Basel the Swiss capital of art, culture, football, logistics and well-being.

He said that one third of all petroleum products and one fourth of all containers enter Switzerland by the Port of Switzerland. Some 60% of goods arriving by ship at the port of Switzerland travel further by rail.

Mr de Langen of TU Eindhoven said that 90% of the freight arriving at the Port of Switzerland is from the northern seaports and 10% is continental. He said that 85% is headed for the Swiss hinterland and 10% for the north of Italy; transit could be increased on the Gotthard route.

As described in our Railweb Report of September 5, 2016, a proposed new terminal, Gateway Basel Nord (GBN), is slated to progressively open between 2018 and 2021.

This photo, which looks roughly south, shows the Swiss-German (CH/D) border and the proposed Gateway Basel Nord (GBN) container terminal. Barges will reach GBN via a new Port Basin 3 to be built under and to the left of the existing motorway. On the right are the orange cranes of the two existing Contargo container terminals in Port Basin 2. The Rhine is visible in the upper right. Switzerland’s main north-south rail route is on the far left. www.gateway-baselnord.com

This photo, which looks roughly south, shows the Swiss-German (CH/D) border and the proposed Gateway Basel Nord (GBN) container terminal. Barges will reach GBN via a new Port Basin 3 to be built under and to the left of the existing motorway. On the right are the orange cranes of the two existing Contargo container terminals in Port Basin 2. The Rhine is visible in the upper right. Switzerland’s main north-south rail route is on the far left. www.gateway-baselnord.com

Holger Bochow, managing director of Contargo Basel, said GBN will handle European-standard, 750-metre trains. He contrasted this to the current track lengths under crane of 300 metres or less the region’s existing terminals in Aarau, Basel-Contargo, Basel-Wolf and Frenkendorf.

GBN will have a direct connection to the Rhine and be able to handle three-layered barges without length limitations. Two remote drivers in an office will operate up to five automatic cranes to assure capacity and redundancy.

The current terminal structure in the Basel area is fragmented and inefficient, Mr Bochow said. Four Swiss Terminal facilities are in operation. Their traffic ranges from 30,000 to 65,000 TEUs a year and their rail modal split for ongoing movements from 10 to 23%.

Mr Bochow said that the consolidated GBN terminal will be better than the current four because it will admit longer trains without shunting, eliminate the need to transfer containers from barges to local dry terminals, and offer more reloadability.

After being unloaded at GBN, containers will be placed on wagons for movement either to Swiss regional intermodal terminals for final truck delivery or on the Swiss wagonload network to industry sidings. The result, Mr Bochow said, will be 20% fewer trucks through Basel by 2030.

Mr Bochow said GBN will also keep the whole logistics chain in Switzerland and therefore off infrastructures in Germany and elsewhere.

Christoph Brutchin of Basel-City canton said that the Port of Switzerland needs efficient terminals with a hub function and that the canton is therefore in favour of the proposed GBN tri-modal terminal.

The container crane of the north Contargo terminal in Basel’s Port Basin 2, which currently ends behind the Ultra Brag terminal at the foot of the motorway viaduct. Port Basin 3 would be built under and beyond the motorway to access the proposed GBN tri-modal container terminal.

The container crane of the north Contargo terminal in Basel’s Port Basin 2, which currently ends behind the Ultra Brag terminal at the foot of the motorway viaduct. Port Basin 3 would be built under and beyond the motorway to access the proposed GBN tri-modal container terminal.

An audience member said that the canton’s support for GBN puts existing, smaller, private terminals in the area at an unfair disadvantage.

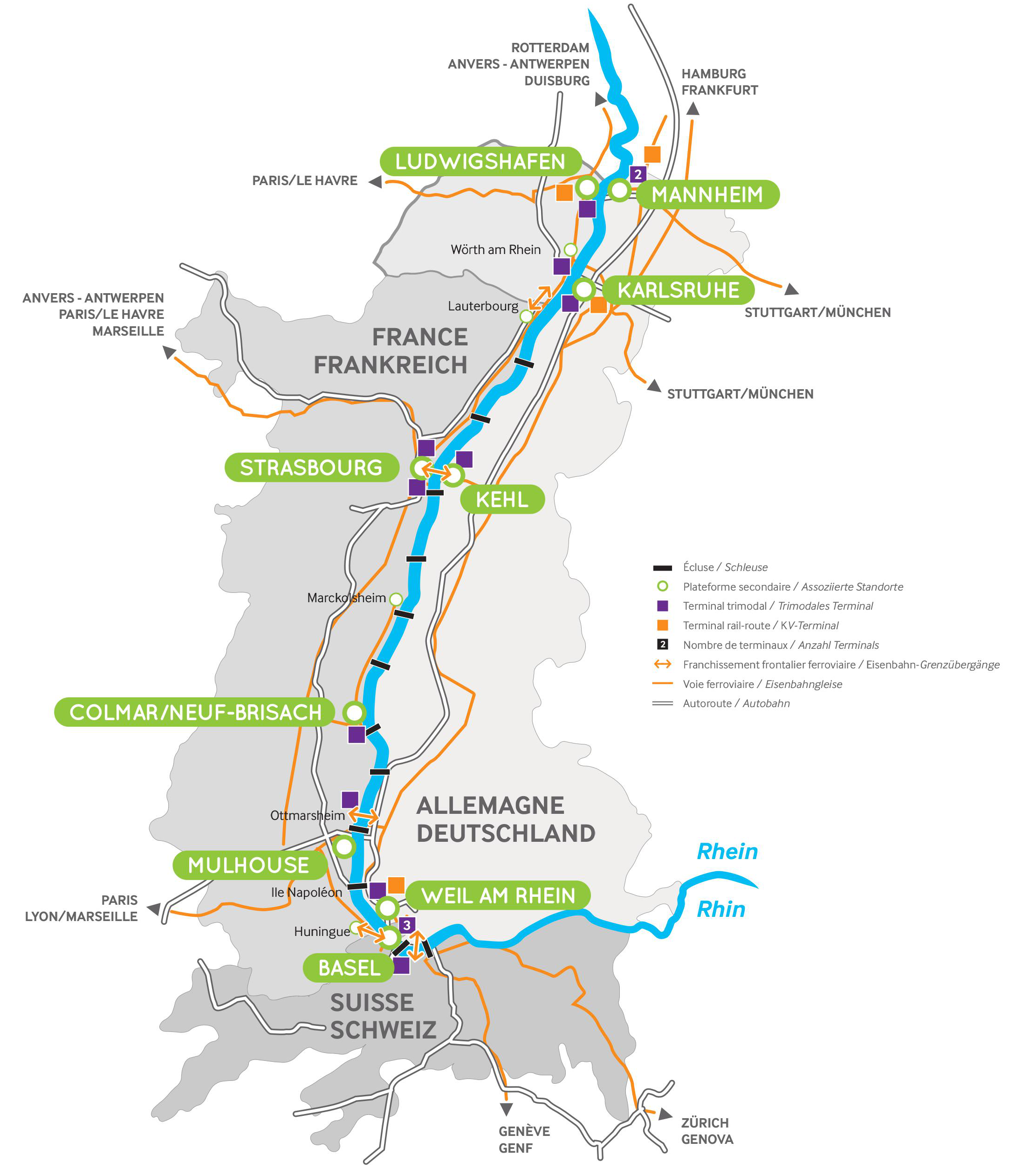

The Port of Strasbourg

Catherine Trautmann, president of the Port Autonome of Strasbourg, said that the port began 90 years ago with a Franco-German treaty between Strasbourg and the German city of Kehl just across the Rhine.

The port currently handles some 8 million tonnes of water traffic per year; it is the second-busiest inland waterway port in France and the fourth on the Rhine. [Comment by Railweb Reports: In terms of container volumes at French inland ports, in 2015 Strasbourg was second only to Gennevilliers (Paris). Both surpassed the seaport of Marseille.]

Ms Trautmann said that the port of Strasbourg can switch to rail in case of high water, and wants to develop dry ports to keep container-hauling trucks out of the Strasbourg city centre. Strasbourg’s ability to load large turbines allowed their production by Alstom (now General Electric) to stay in Europe.

A new actor in inland ports: DP World

Andreas Janetzko said that the new DP World inland Europe division so far includes the following inland ports: Antwerp East, which is 35 km from the main port, Liège, Mannheim, Germersheim and Stuttgart.

DP World’s European inland terminals and their hinterland. Andreas Janetzko presentation

DP World’s European inland terminals and their hinterland. Andreas Janetzko presentation

Mr Janetzko said that in Stuttgart, DP World is the designated terminal for Mercedes-Benz, so all carriers and forwarders working for Mercedes-Benz must use DP World’s terminal even though the latter’s direct customer is a deep-sea carrier. But DP World Stuttgart is terminal-neutral and port-neutral regarding other ports.

DP World has organised a mixed rail-and-water link from an inland port: With their own and external assets, they have a line from Ludwigshafen by rail to the Croatian port of Rijeka and from there by sea to Turkey.

Infrastructure links to inland terminals

Rail infrastructure links to inland terminals

Mr Janetzko said that DP World wants to take better advantage of the several rail freight corridors they are on.

Mr de Langen of TU Eindhoven said that ports are less developed than their hinterland links, such as the new Gotthard tunnel and the 55-km Brenner base tunnel between Austria and Italy slated to open in 2025. By law, two thirds of the capacity of the new Gotthard tunnel are reserved for freight.

Felix Günther, lecturer at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich, presented a study on corridors and the contrasting interests of different levels of government:

- EU: no trade barriers; free circulation of people and goods; precedence of freight traffic.

- EU-member and other states (such as Switzerland): connect metropolitan areas well; regional development.

- Regions: promote public transport; this is the messiest level, as it entails development along railway lines.

The EU’s CODE24 project for the development of the Rotterdam-Genoa corridor, which ran from 2010 to 2015, sought to create common knowledge about how corridors function and involved some 300 actors. Part of the project involved an intercontinental comparison of three corridors:

- The Acela line in the Northeast US (100 million people on the corridor)

- Europe’s Corridor 24 (70 million)

- The Shinkansen corridor (150 million)

Among these three corridors, only Corridor 24 has significant freight. Mr Günther described three categories of investment and said that about €35 billion is foreseen for each:

- Rail projects on the north-south corridor by 2050, mostly in the south.

- Port projects, mostly in the north.

- Urban development of rail nodes (logistic centres) distributed evenly from north to south.

A central objective of planners, Mr Günther said, is to avoid “cathedrals in the desert”. Part of the CODE24 project was therefore “collaborative assessment workshops” that combined all viewpoints in the Arnheim-Oberhausen area in 2010-2011 and the Frankfurt-Mannheim area in 2011-2014. A similar workshop for the area comprising Milan and Switzerland’s Italian-speaking Ticino region will start in 2017 and another is foreseen for the Basel-Jura area.

Impact of the new Gotthard rail tunnel

From the viewpoint of the Milan-Ticino area, Mr Günther presented the impact of the new 57-km Gotthard rail tunnel, which opened in 2016.

He said that Milan is two cities: 2.8 million people in the central Milan area and 2.2 million in the area north of there and south of Ticino. Ticino is hemmed in by two lake systems and receives lots of Italian commuters. [Comment by Railweb Reports: According to the NZZ newspaper, as of 2015 about 63,000 or over a third of those employed in Ticino lived in Italy.] Intercity trains, freight trains and trains operating within the metropolitan area compete for the available capacity. Main conflict points are level crossings, single tracks and noise.

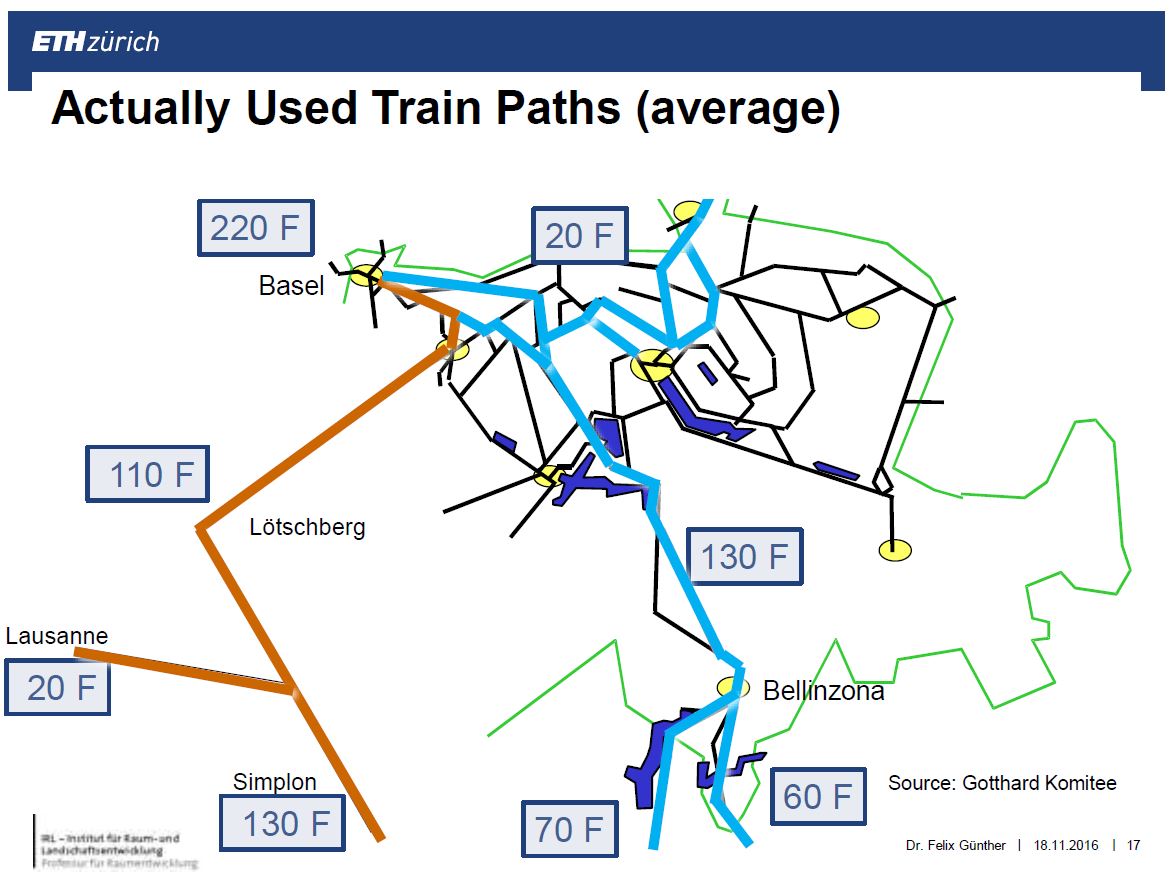

Current average path use for freight trains per day. Felix Günther presentation

Current average path use for freight trains per day. Felix Günther presentation

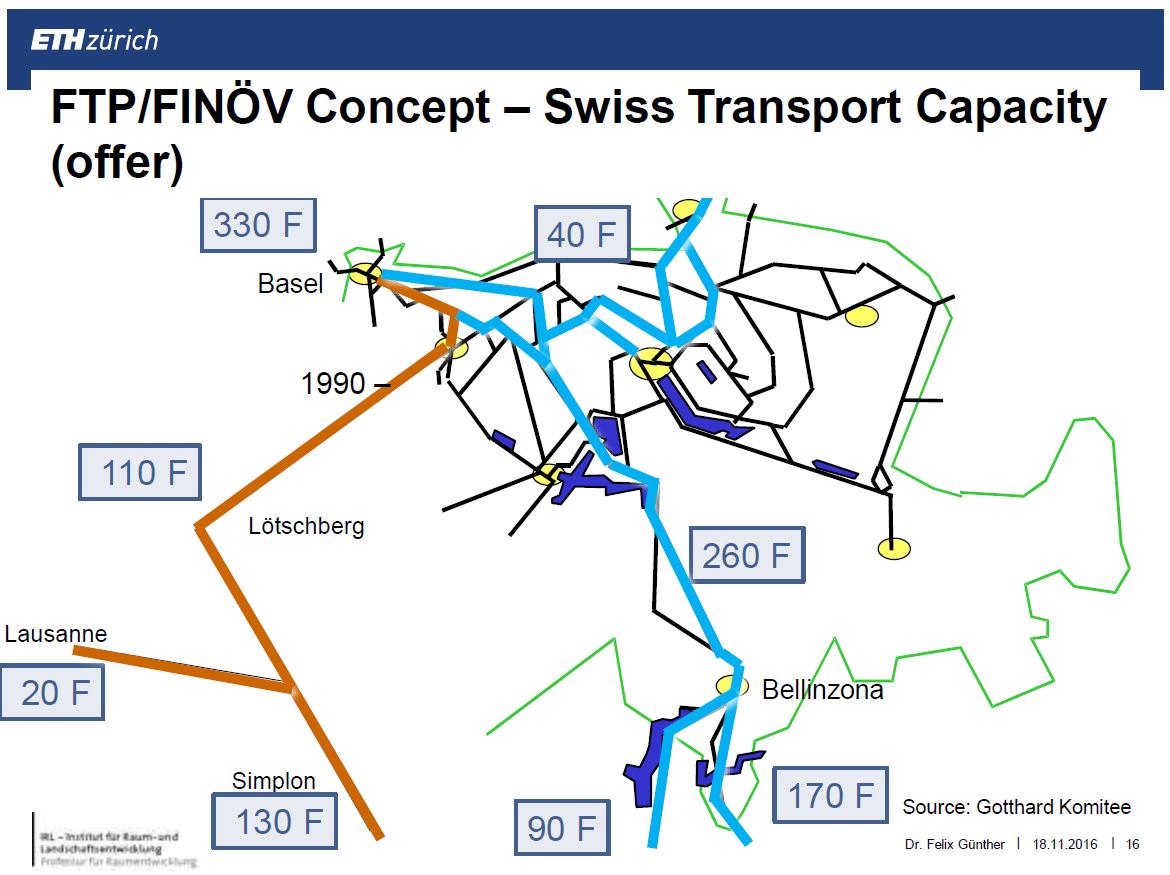

The original 1990 plan, Mr Günther said, was to run two hourly fast passenger trains through the new Gotthard tunnel, one right after the other. This would have allowed 300 slower freight trains a day through the tunnel. Now passenger trains are every half hour. This leaves capacity for only five freight paths between passenger trains or a total of 260 freight trains a day.

The main bottlenecks are now south of the new Gotthard tunnel and mostly in Italy. Work to gradually increase capacity will allow daily freight trains to increase from today’s 130 on the Gotthard route to 260, including an increase from 70 trains to 90 on the western route to Gallerate and from 60 trains to 170 on the eastern route via Como.

Path capacity for freight trains per day after improvements to the branches into Italy. Felix Günther presentation

Path capacity for freight trains per day after improvements to the branches into Italy. Felix Günther presentation

On the other main route from Switzerland into Italy, the Lötschberg-Simplon route to the west, Mr Günther said, the number of daily freight trains is expected to remain stable at the current 110 trains a day that now run through the 35-km Lötschberg base tunnel, which opened in 2007 and feeds the Simplon tunnel, whose 130 daily freights include 20 to/from Lausanne.

Mr Günther stressed the need to coordinate current and future terminals with future rail-line improvements. His motto was: “No tracks without integrated territorial strategy”.

Water hinterland links

Mr Maelissa of the barge operator Danser said that the EU has 40,000 km of navigable waterways and 200 inland ports representing 6.9% of EU freight value. This percentage is much higher in countries with good waterways.

The biggest users of inland waterways are at the ports of Rotterdam, Antwerp and Constanta, followed at a distance by Bremerhaven and then Hamburg.

Mr Janetzko of DP World said that barge works when the water is not too high or low, but you also need a rail alternative. He wants to connect DP World’s inland terminals to the proposed Seine–Nord Europe Canal in France, whose status is uncertain.

Transport services to inland terminals

Connectivity between deep-sea ports and inland nodes

Jeroen Bozuwa presented the database of intermodal links in EU developed by www.IntermodalLinks.com. The database comprises 150 operators, including intermodal operators (barge, rail, shortsea and feeder) and ferry and roll-on-roll-off (RORO) operators. They offer some 14,000 direct terminal-to-terminal services between 800 terminals in 48 countries. The database does not include lines from China yet. It covers regular services, defined as at least weekly.

Of the 150 intermodal operators, 44% are rail, are 29% barge and 27% shortsea or feeder. Of the 14,000 services, 53% are short-sea or feeder, 35% are rail and 12% are barge. [Comment by Railweb Reports: This means that on average, each barge operator offers 38 services, each rail operator 74 and each short-sea or feeder operator 181.]

“Planning a route with Intermodal Links is as easy as using Google maps”, Mr Bozuwa said. From a given origin point, the program’s map colour-codes terminals to show the number of days to reach the terminal given available service. You can also add a non-existing service to see how it would improve transit times betweeen different terminal pairs.

The program can also colour-code a region to show the number of competing operators when coming for example from Hamburg. This may indicate the price and service pressure on operators.

The Intermodal Links database has 12 rail terminals in Rotterdam. In terms of services per week, the share of the two largest rail terminals in Rotterdam is less than 50%, which mean “huge interdependence and coordination issues”, Mr Bozuwa said.

Loading dry bulk goods (possibly construction debris) in Basel.

Loading dry bulk goods (possibly construction debris) in Basel.

Mr Bozuwa said that the market share of incumbent train operators is dropping in many ports.

The database shows that over 25% of the barge services cover less than 100 km and over 50% less than 200 km. Some 10% of the rail services cover less than 200 km. This is noteworthy given that the EU goal of moving 30% of freight by 2030 and 50% of freight by 2050 by water and rail only applies to movements over 300 km.

Mr Bozuwa also reached these conclusions from the Intermodal Links database:

- The larger the overall rail intermodal share at a port, the shorter the haul over which a rail service remains economical because of lower unit costs in terminals and mutualisation of rail pickup and delivery at different terminals within the port.

- Rail service frequency tends to decrease with lengthening haul.

- On average, barge services are half as frequent as rail, and their lengths of haul also half of rail’s.

- Few routes have more than one operator.

- Intermodal operators do not routinely start new lines.

Mr Bozuma also broke down services by mode and type:

| Service type | Rail | Barge |

| Port ⇔ Inland node | 64% | 82% |

| Port 1 ⇔ Port 2 | 10% | 15% |

| Inland node 1 ⇔ Inland node 2 | 26% | 3% |

| Total | 100% | 100% |

Reliability of hinterland services

Matthijs von Doorn, director of logistics for the port of Rotterdam, said their website maintains figures showing the schedules and reliability of rail and barges. He said that the efficiency of a port gets translated into price: bad barge and rail connections will be reflected in higher trucking costs. On the other hand, more big ships mean fuller and more direct trains and barges.

Role of major actors in inland terminals

Inland terminals and the role of government

Mr Lochman of the railways’ CER said that EU states and other states do not give the same attention to terminals, ports, inland waterways and rail infrastructure as they do to road. Ms Trautmann of Strasbourg said inland waterway ports tend to be ignored at European level.

A consensus nevertheless emerged among attendees that the importance of the inland terminal is growing and so is its recognition.

Mr van den Bosch of the European Federation of Inland Ports said that because of confidentiality concerns, Eurostat has no data on inland terminals. He said that logistic actors need support from EU in the following areas:

- Inland ports

- Rail freight, including both intermodal and wagonload

- Inland-waterway-friendly access at deep-sea ports

- A reliable framework for state aid

Height warning at the entrance of Basel’s Port Basin 2. Dams and locks along the Rhine regulate the water’s height, but episodes of high water still occur.

Height warning at the entrance of Basel’s Port Basin 2. Dams and locks along the Rhine regulate the water’s height, but episodes of high water still occur.

Mr Maelissa of the barge operator Danser called for more efforts to store water to avoid periods of too high or too low water, but warned that the €500 billion needed to complete the Trans-European Network for Transport (TEN-T) are not forthcoming.

An audience member said that his company runs and promotes public-private partnership (PPPs) but that EU governments are no longer able to support PPPs. He pointed out that Uber and Airbnb have nothing to do with PPPs.

Mr Maelissa said he was opposed to subsidies to encourage cooperation among shippers. “What we earn on inland waterways is so lousy that we are forced to cooperate”, he said. An audience member said that subsidising shippers to cooperate is “like asking some children in kindergarten to talk together”.

Mr Lochman of CER said that internalisation of external costs requires that roads, like railway infrastructure, be user-paid.

Mr Lochman also discussed the mandate to finance the European standard signalling system ERTMS. If the EU wants a single railway space, he said, the EU must find a way to finance the ERTMS mandate over the next 10 to 15 years. A related problem is the different levels of support in different EU states for on-train implementation of ERTMS, which means discrimination among railway undertakings. The EU must solve this problem, he said.

The commitment to rail is weaker within EU states than at the European Commission (EC). “We don’t fail in Brussels – we fail in the capitals”, Mr Lochman said.

In the context of the Connecting Europe Facility (CEF), Mr Lochman said, the EC has published its 2016 call for proposals for freight transport, including:

- €20 million for modal shift, multimodal integration, efficiency of supply chains, and connections to and between existing terminals by green modes.

- €20 million for multi-modal logistics platforms, including accommodating 740-metre trains.

Mr Lochman said that he opposed operating subsidies, but did see a need for investments and policies to internalise external costs and create a level playing field between modes.

He reported data from the different EU states that show a perceptible, .30 correlation between investment in rail infrastructure per line kilometre between 2002 and 2012 and growth or decline of rail modal share.

[Comment by Railweb Reports: the European Union is playing an essential role in assuring interoperability and competition between freight train operators that benefit shippers and the public.]

Inland terminals and the role of the middleman

An audience member asked whether the trend toward operators’ making data directly available to shippers (or “cargo owners”) would “cut out the middleman”. A freight forwarder in the audience replied that freight forwarders still have figure out how to move your container, which is why freight forwarders are still growing.

Mr Neumann-Lezius of Kühne + Nagel said that providing information to shippers does not mean that shippers can take over the operations performed by middlemen. Alexander van den Bosch of the European Federation of Inland Ports called the existence of 4LPs and freight forwarders proof of shippers’ lack of knowledge. Discussion yielded a consensus that that middlemen have to support shippers, not educate them.

Mr Lochman of CER said that transport companies of all modes are increasingly trying to be logistic operators. Rail representatives have to start working on shippers now in order to have an effect in 5 to 10 years. [Comment by Railweb Reports: rail lobbyists like CER also educate government officials and policymakers.]

A fragmented forwarder market

Mr Neumann-Lezius said that Kühne + Nagel is the biggest freight forwarder in the world for ocean freight, but that DHL is ahead when you include air freight.

Mr de Langen of TU Eindhoven pointed out, however, that Kühne + Nagel and DHL account for only 2 to 3% of world freight, which indicates the sector’s fragmentation. This means both local capacity problems and bad fill rates because matching is hard.

Mr Van Breedem of TRI-VIZOR said that logistics companies are become ever more numerous and smaller. The number of mergers and acquisitions is still very limited because profits are too low – 2% at best.

Need for and barriers to cooperation

The conference saw several discussions of the need for and barriers to cooperation between port actors. Mr van den Bosch of the European Federation of Inland Ports saw a lack of collaborative planning in the global container business. The big problem, he said, was getting firms to share data that gives them a competitive advantage. Mr Van Breedem said that cooperation between entities may require changes to antitrust laws.

Two cranes working together to transload dry bulk freight from a barge to railway wagons in the Port of Switzerland at Basel on April 27, 2016.

Two cranes working together to transload dry bulk freight from a barge to railway wagons in the Port of Switzerland at Basel on April 27, 2016.

With regards to inland ports, Mr Neumann-Lezius of Kühne + Nagel said that more sharing in a port reduces intra-port competition but improves the port’s competitiveness against others. But collaboration may conflict with antitrust laws and customer desires for competition.

An audience member said for the last six years, Constanta has been trying to create a network of Danube reports, including German and Austrian inland terminals, instead of just competing. Collectively, their traffic is low.

Ms Trautmann of Strasbourg said that the upper Rhine ports, of which the northernmost are Ludwigshafen and Mannheim, have now formed an association that has allowed development of a Rhine Port Information System (RPIS – see below). She said the ports had to get beyond their habit of not sharing information.

Examples of good practice with inland terminals

An integrated European distribution network: Stanley Black & Decker

Filip Degroote is director of transport for Europe, the Middle East, Africa, Australia and New Zealand for Stanley Black and Decker (SB&D). SB&D spends some $435 million a year on transport, he said. They have nine distribution centres in Europe: one each in Belgium, Poland, Spain and the UK, two in France and three in Italy. Each centre handles almost all products of the SB&D group.

Ten European SB&D manufacturing plants are located in different places from the distribution centres, which also handle inbounds goods from the US and from Asia, where SB&D has 28 more manufacturing plants. SB&D works with a mix of freight forwarders, including Kühne + Nagel, and also directly with carriers.

The BCTN Meerhout inland terminal in Belgium. Filip Degroote presentation

The BCTN Meerhout inland terminal in Belgium. Filip Degroote presentation

SB&D’s new distribution centre in Tessenderlo, Belgium, has 60,000 m² and is expandable to 75,000 m². The logistics operator BCTN operates a large container terminal at Meerhout, 8 km away on the Albert Canal. With its 130,000 m2 terminal, a 350-metre quai for barges, two 320-metre rail tracks and its own staff of 70, BCTN’s Meerhout office serves as a “last-mile captain” for SB&D in Tessenderlo.

On the basis of advance information on incoming ships and their contents, SB&D advises BCTN Meerhout about hot containers or hot items within a container. In its role as last-mile captain, BCTN Meerhout:

- Makes appointments for deliveries to the Tessanderlo distribution centre.

- Deals with congestion in the port and on the highway.

- Manages multiple carriers and forwarders for both import and export flows.

- Organises return of empty containers.

SB&D uses key performance indicators (KPIs) on last-mile operations. Mr Degroote said that the last-mile captain has allowed reduction of fuel consumption and quai rent. The goal is to use barge (and truck for flexibility) to assure five days between a ship’s docking and the goods’ presence in the warehouse of SB&D.

Mr Degroote said SB&D must balance working capital against transport costs. The profit- and-loss structure of a large company may lead to be decisions that are suboptimal from the viewpoint of SB&D as a whole. His job is to overcome such phenomena.

Cooperation among ports: the Rhine Port Information System

Stefan Wiech of Hamburg Port Consulting (HPC) presented an EU project of the upper Rhine ports to develop a barge management system from Basel to Mannheim. HPC is managing the project, but not developing it. Goals of the Rhine Port Information Systems (RPIS) are to:

- increase competitiveness through IT exchange,

- eliminate port congestion by scheduling barge calls and

- ease border crossings.

Mr Wiech said that congestion is worst on Fridays outside Rhine ports for northbound barges. The RPIS slot management system coordinates barge calls. Barge operators announce visits. All calls are planned with one IT system for all upper Rhine ports. Updates based on real-time barge positions allow an alert when a slot is in danger due to a barge’s delay.

Pilot implementation began in 2014 at some southern upper Rhine ports. RPIS entered service on September 1, 2015. In the course of 2016, the system was rolled out to other upper Rhine ports. RPIS is now at the end of its test phase. In 2017, the system will go fully live and undergo functional and geographical extension.

The basis for RPIS is a strategy of openness and modularity. The ports of Rotterdam and Antwerp are also involved; Antwerp developed the first module.

Mr Wiech said that small ports north of Mannheim may later be added to RPIS. Large parts such as Duisburg do not need it because, unlike the small ports, each of which are one stop along the route of a barge, Duisburg will tend to take a barge’s whole cargo.

The French inland waterway’s agency VNF has an estimated time of arrival (ETA) calculation system that will be integrated within RPIS. Mr Maelissa of barge operator Danser pointed to a need to integrate locks and the waiting time at them, which GPS does not show you. The owners of RPIS want to link to ocean shipping lines and supply chains of clients. [Comment by Railweb Reports: “supply chains” implicitly includes trucks, but rail operators should also be involved.]

Ms Trautmann of the Port of Strasbourg said that rail and water are often left out of the development of intelligent transport systems (ITS) for trucks.

George Raymond can be reached at graymond@railweb.ch.

© Copyright 2017 George Raymond. All rights reserved.

Back to Railweb Reports